Q. Historians often refer to King Richard’s supposed treatment of Sir Henry Wyatt. The story of Wyatt’s ‘imprisonment’ is a good example of how myths have been reported as facts, and how those facts have subsequently influenced later writers. A recent example of myth inspiring fiction occurs in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (2009). On pages 324 – 325, the author discusses Henry Wyatt’s imprisonment in the Tower of London and his subsequent torture, directed personally by Richard III. Is there any historical evidence to support this?

A. No. Although, to the author’s credit, she is merely reporting the ‘facts’ as they appear in other historical works. Wyatt was an agent of Henry VII who later became a councillor to Henry VIII, but this story actually relates to his recorded imprisonment and torture in Scotland which was of course a separate country with its own reigning monarch, James III (1451–1488). He was incarcerated in dismal conditions in Scotland from c.1483 to 1485. When Henry VII became king he helped ransom him. There is no known supporting evidence that Henry Wyatt was ever taken into custody by Richard III or that he was imprisoned in the Tower of London in Richard’s reign. His alleged incarceration and torture at the hands of Richard is derived from a family tradition which exaggerated Wyatt’s already colourful career as a faithful Tudor supporter who suffered for his loyalty. The story was copied into the Wyatt family papers in 1731 from a lost original.

To discover more about Henry Wyatt and the myth concerning his torture by Richard III, you can read Annette Carson’s seminal paper, ‘The Questionable Legend of Henry Wyatt’ (2012) here. The paper was published in 2012 in the Ricardian Register of the American Branch of the Richard III Society. It was published in shortened form in the Society’s Ricardian Bulletin (September 2011).

With our very grateful thanks to Annette Carson for her kind permission to publish this paper.

You can also view this paper on Annette’s website here.

Q. Is it true that Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor (1459-1519), did not believe that Richard III had illegally set aside the sons of Edward IV so that he could rule himself, and his support of Richard was related to the illegal seizure of his own young children, Philip (6) and Margaret (4)?

A. Yes, this is true and is best answered by American researcher, Susan Troxell, in her article: ‘The Last Knight: the art, armor, and ambition of Maximilian I on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’, Ricardian Bulletin (December 2019), pp.51-56. Susan records on p.56, fn.2:

‘Maximilian’s 1484 embassy to Richard III requested military aid to defend Flanders, and proposed a formal alliance between England, Burgundy and Brittany against France. At the time of this diplomatic overture, Maximilian’s only son and heir Philip had been forcibly taken from his custody by the burghers of Bruges, and Maximilian was denied any access to the six-year-old boy as well as his four-year-old daughter Margaret. Maximilian’s missive to Richard III complained bitterly and repeatedly of the ‘intermeddling’ injustice done by removing Philip from his protection, and setting up a false governing council in Philip’s name in Bruges. The missive accused the burghers of using lying words, corruptions, and subtle unlawful laws to get into their hands and power both of Maximilian’s children, accusing them of an ambition to rule and govern, and spreading lies about Maximilian’s intentions to usurp his son’s titles. Gairdner, Letters and Papers, vol.2, pp.8-9, 11-12, 20, 29, 37-8. Given that Richard III was similarly rumoured by some of taking wrongful custody of Edward IV’s sons and having had a secret agenda of setting them aside and ruling himself, it would seem remarkably tone-deaf to emphasize this type of wrongdoing in a diplomatic embassy seeking a formal alliance with the English king less than one year after his accession. There were other grounds to show the burghers’ actions were illegal, namely, Mary of Burgundy’s last will and testament which provided that Maximilian should govern in Philip’s name during his minority. Maximilian’s strategy seems to imply that he did not find the aforesaid accusations against Richard III credible, and was directly appealing to Richard’s indignation at having his honor and motives questioned by false rumors.’

The Missing Princes Project note: Mary of Burgundy (1457-1482) was wife to Maximilian and mother of Philip and Margaret.

Our grateful thanks go to Susan Troxell for her very kind permission to publish this information here.

Susan is a retired lawyer and the non-fiction librarian of the American Branch of the Richard III Society, and has written numerous articles for the Ricardian Bulletin and Ricardian Register.

Q. Many of the acts passed by King Richard, in his only Parliament of 1484, were specifically designed to benefit the underprivileged. However, it has been asserted by a number of traditional historians that these acts cannot be attributed to the king himself, and that they were simply a reflection of government in motion. Is this true?

A. No, this is not the case and seems to be yet another example of a modern myth promulgated about the reign of King Richard III. The acts in question reflect Richard’s personal concern for justice and the common weal, a concern he had demonstrated as duke of Gloucester and which he continued to exhibit as king. It is also a profound example of the king’s professed desire for the impartial administration of justice. Please refer to the following article by author and historian, Matthew Lewis, ‘Richard III in Parliament’, Ricardian Bulletin (March 2020), pp.34 –36. You can now read Matthew’s paper here.

In 2002, Matthew Lewis graduated in Law from the University of Wolverhampton.

Our grateful thanks go to Matthew and the editor of the Ricardian Bulletin magazine, John Saunders, for their kind permission to publish this paper.

The first detailed examination of Richard III’s statutes was published by the Oxford academic H.G. Hanbury in the American Journal of Legal History in 1962 (please see below). Hanbury was Vinerian Professor of English Law at the University of Oxford (1949-1964) and with A.L. Goodhart edited the final volumes of the History of English Law by Sir William Holdsworth. He also published Essays in Equity (1934), Modern Equity (1935, in thirteen editions by 1989) and English Courts of Law (1944; fifth edn, 1979). You can now read Hanbury’s legal analysis of Richard’s parliamentary legislation here (in extract form). Please note: sub-headings have been inserted to ease navigation for the general reader. To delve further into the technicalities of King Richard’s laws, you can read Hanbury’s complete legal analysis here. Source: H.G. Hanbury 'The Legislation of Richard III', American Journal of Legal History, vol. 6 (1962), pp.95-113.

‘This paper will have served its purpose if it has succeeded in portraying him [Richard III] as a singularly thoughtful and enlightened legislator, who brought to his task a profound knowledge of the nature of contemporary problems, and an enthusiastic determination to solve them in the best possible way, in the interests of every class of his subjects.’

H. G. Hanbury, Q.C. D.C.L. Vinerian Professor of English Law, University of Oxford (1949-1964)

‘We have no difficulty in pronouncing Richard’s parliament the most meritorious national assembly for protecting the liberty of the subject and putting down abuses in the administration of justice that had sat in England since the reign of Henry III’

Lord Campbell, First Baron Campbell, Lord Chancellor and Lord Chief Justice (1779-1861)

Q. Why did Richard III never declare his innocence with regard to the fate of the sons of King Edward IV?

A. Following the death of Queen Anne Neville on 16 March 1485, rumours arose that King Richard had poisoned his wife in order to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York. It is recorded that two weeks later, at the Priory of St. John in Clerkenwell, King Richard openly denied these rumours. If the king was prepared to publicly deny a rumour concerning Elizabeth of York, it seems clear that the propagation of falsehood and rumour was something he took very seriously. Would it not therefore be in keeping for Richard III to make a public declaration with regard to his involvement in the disappearance of his nephews?

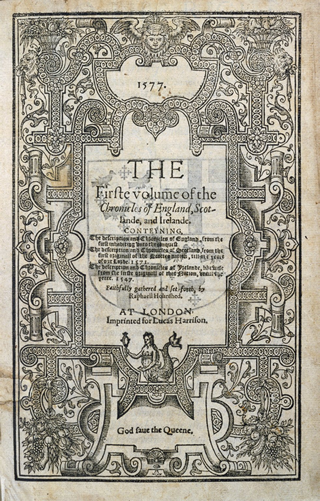

In his Chronicle, Raphael Holinshed records just such a declaration made by King Richard during his Parliament, which sat from 23 January to 20 February 1484. Interestingly, Holinshed is the only Tudor Chronicler to record this potentially vital piece of information (see question below). He records: ‘For what with purging and declaring his innocence concerning the murder of his nephews toward the world…’ although he cannot resist adding the Tudor spin that this was done simply to acquire the favour of the people. See: Raphael Holinshed, The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1577), Vol 2, p.1405.1 Following Holinshed’s death in 1580, an extended edition of his Chronicles was published in 1587. See: The Third Volume of Chronicles by Raphael Holinshed augmented to the Year 1586 (London, 1808), p.422.

The following proclamation issued by Richard III on 6 December 1484 can be taken as further evidence of the king’s determination to confront rumours and untruths intended to undermine his kingship.

"Forasmuch as we be credibly informed that our ancient enemies of France, by many and sundry ways, conspire and study the means to the subversion of this our realm, and of unity amongst our subjects, as in sending writings by seditious persons with counterfeit tokens, and contrive false inventions, tidings, and rumours, to the intent to provoke and stir discord and disunion betwixt us and our lords, which be as faithfully disposed as any subjects can suffice. We therefore will and command you strictly, that in eschewing the inconveniences aforesaid you put you in your uttermost devoir of any such rumours, or writings come amongst you, to search and inquire of the first showers or utterers thereof ; and them that ye shall so find ye do commit unto sure ward, and after proceed to their sharp punishment, in example and fear of all other, not failing hereof in any wise, as ye intend to please us, and will answer to us at your perils." (British Library Harleian Ms 787, f2b)

1. With thanks to Michael Alan Marshall for alerting us to this original source (6.7.15).

For more on King Richard’s declaration of innocence from Holinshed see Case Study page, Part One paper here.

Q. Was the history of King Richard III rewritten during the Tudor period?

1483 is a key period for the mystery surrounding the Princes. It is essential to discover the truth behind the many stories and myths relating to the events of that year if we are to understand the extent to which history was later re-written. Dr Judith Ford’s revealing article on Ralph Shaa – A 'Vale of mysrye'? The will of Dr Ralph Shaa’ - published in the Ricardian Bulletin (September 2021), pp 52-55, is a part of The Missing Princes Project’s investigations. In this case the new assessment of the will strongly indicates that later non-contemporaneous suggestions that Shaa’s reputation was damaged by his public support for Richard III were unfounded.

You can now read Judith’s illuminating article here

With thanks to Judith Ford and Alec Marsh, editor of the Ricardian Bulletin, for their permission to publish this article here.

Q. Do we know whether the censorship and spin practised in the early Tudor period continued into the Elizabethan age?

A. It seems that control of information continued well into the Elizabethan age. As discussed previously, Raphael Holinshed (c.1525-1580), a Cheshire man educated at Cambridge University, wrote a three-volume compilation of Chronicles which became the standard history of England. The first edition was published in 1577, with an enlarged second edition appearing ten years later (after Holinshed’s death). Holinshed’s aim was to ‘keep an especial eye’ on the truth. However, it is interesting to note that the work was heavily censored by Elizabeth I’s Privy Council. As also mentioned above, Holinshed is the only chronicler to record King Richard’s public declaration of innocence concerning the fate of the sons of Edward IV. A declaration made at the time of the king’s Parliament in January-February 1484. Did Holinshed discover this information whilst at Cambridge University; a body closely associated with the Yorkist king, and did this line of text somehow evade Elizabethan censors? As a result of this censorship, Holinshed’s Chronicles subsequently followed Hall’s Chronicle for the history of Richard III. Hall’s Chronicle was based on a corrupted version of Thomas More’s account (published by Grafton). William Shakespeare owned a copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles and wrote his Tragedy of King Richard III in c.1593 during the reign of Elizabeth I, who died in 1603. In terms of censorship, it is recorded that during her reign, the last Tudor monarch embargoed any performances of Shakespeare’s Richard II (written c.1595) for fear that such an open visualisation of the overthrow of a reigning monarch, may have repercussions for her own rule.

Thomas More’s account, discovered amongst his papers following his execution by Henry VIII in 1535, and published posthumously by his son-in-law, would become the definitive text for the history of Richard III. As a child, More had been a page in the household of John Morton, whose strong Lancastrian tendencies made him a known detractor of King Richard.