Sir James Tyrell’s Confession – Fact or Fiction?

First published in the Ricardian Bulletin magazine of June 2021, pp.44-53, this article drills down into exactly what is known about Sir James Tyrell’s confession. As a result, it now brings to light materials surrounding Tyrell’s story, and his wider family, that has, until now, been omitted from the history books. This paper now sets the record straight. You can read the full article here.

Extract:

A proper evaluation of the veracity of Thomas More’s account of the confession of Sir James Tyrell (and John Dighton) to the murder of the sons of Edward IV is dependent upon a consideration of the following factors.

Firstly, the existence of any confirmatory evidence. As England’s former Chancellor, Sir Francis Bacon tells us, this does not exist. No declarations or Proclamations were made by King Henry, nothing reported in Parliament or recorded and published by the government of the day. What accounts we do have are contradictory and incoherent. Polydore Vergil claimed that Tyrell murdered the sons of King Edward IV so that a younger son of King Edward’s sister could rule at some future date. Such remarkable foresight and political cunning is not borne out by the historical evidence, nor supported by Tyrell’s long and faithful service to three reigning monarchs.1 Moreover, Vergil’s first published account of his history of the reign of Henry VII (Basle edition, 1534), includes the following statement which was removed from later publications:

‘It was generally reported and believed that the sons of Edward IV were still alive, having been conveyed secretly away, and obscurely concealed in some distant region.’2 Hay records this as ‘a certain secret land.’3

It must also be noted that Vergil uses the words ‘restore’ and ‘restored’ when reporting the identities of the two Pretenders to the English throne. Did these descriptors also slip through the editorial net?

We also have evidence that members of Tyrell’s wider family supported the Pretender, Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be the youngest son of Edward IV. In 1498, Sir John Speke was fined the enormous sum of £200 by Henry VII for ‘aiding and comforting’ the Pretender.4 W.E. Hampton records:

‘Speke's adherence to Warbeck suggests that even that branch of the Arundell family which was hostile to Richard III had no knowledge of the certain deaths of the sons of Edward IV nor suspicion of Sir James's responsibility in the matter....’5

Significantly, we also have evidence of Tyrell’s close family support of Warbeck, and their confirmation that he was the son of Edward IV. Tyrell’s first cousin,6 Sir Thomas Tyrell of Essex and Hertfordshire (c.1453-1510), was one of a number of conspirators in the Warbeck rebellion which aimed to assassinate Henry VII. One of Henry’s spies recorded a remarkable conversation where Sir Thomas Tyrell is unequivocal that the boy is King Edward’s son.7 Sir Thomas had been an esquire of the body to Edward IV and Richard III,8 and was also the nephew of Elizabeth Tyrell, Mistress of the Royal Nursery. It seems, therefore, that Sir Thomas, like many others in the Warbeck conspiracy had connections with the Yorkist royal family, its household and nursery.9 Despite written evidence of his treason, together with two witnesses, it is quite remarkable that Sir Thomas was never brought to trial, when the likes of Sir William Stanley, King Henry’s Chamberlain, had been summarily executed for uttering some words in support of the boy. Interestingly, today the ODNB records no mention of Sir Thomas Tyrell’s part in the conspiracy, or the family’s identification of ‘Warbeck’ as King Edward’s son.10 We must also add to this the Tyrell family tradition that the boys stayed at Gipping with their mother (Elizabeth Woodville) ‘by permission of the uncle.’11

Moreover, we must also consider, as Annette Carson established, that no Masses were said for the souls of the boys.12 This, in terms of the period’s religiosity, is highly significant.

Secondly we must consider chronology. Henry VII had been king and master of the Tower of London from the summer of 1485, but it had, apparently, taken seventeen years to produce a story of any kind which accounted, ‘as the king gave out’, for the disappearance of the princes. Importantly, the story appeared at a time of genuine crisis for the early Tudor dynasty. Henry VII’s son and heir had died unexpectedly (as had his third son, Prince Edmund), while the king himself was ill and deeply unpopular. The marriage of Catherine of Aragon to Henry’s remaining son (Prince Henry) therefore assumed some importance in securing the dynasty’s future. Did Henry VII therefore feel compelled to reassure the Spanish monarchs of his continued hold on the throne by finally bringing the mystery of the princes to a definite conclusion, thereby securing the ground for a future marriage between Prince Henry and Catherine?

Thirdly, we must take into account what we know about Sir James Tyrell. He served three kings faithfully and was placed in positions of trust. His biographer, the Rev. Sewell, said of him,

‘We have abundant evidence of the greatness, reputation and personal bravery of Sir James Tyrell. He was one of the foremost, and certainly one of the ablest men of his day.’13

So was it one of Tyrell’s royal duties which had made him the ideal candidate for the confession story. As Master of the Henchmen, Tyrell was in charge of the young boys and teenagers at King Richard’s court, the squires and pages required for ceremonial duties and knightly training. Did this role provide a connection and give credence to the story? Or was it because Tyrell’s cousin, Elizabeth, was Mistress of the Royal Nursery? Both positions would have placed Tyrell within the orbit of the children of Edward IV. Or was it because he was responsible for the discovery and delivery of Buckingham’s heir during Richard’s reign? Moreover, no contemporary source from Tyrell’s lifetime raised any concern regarding his proximity to children or their safety in his care. Interestingly, even today, the ODNB fails to record any mention of Tyrell’s own children, four of whom married.14

Finally, we must also consider what we know about More’s unfinished manuscript; specifically that it is written as a dramatic narrative and remained unfinished, untitled and unpublished. That it was not taken seriously as a ‘history’ can perhaps be further deduced from the published work of More’s brother-in-law John Rastell in 1529. As C.S.L Davies and Matthew Lewis establish,15 Rastell published his history of England in The Pastime of People,16 yet fails to record Tyrell, his confession or any involvement in the murder. This, even though his brother-in-law (More) was a prolific writer and publisher, and Rastell also an author and publisher. Would More not have known about Rastell’s forthcoming great publication, or mentioned what he knew. What a scoop this would have been for his publisher brother-in-law. At the time More had also been made Lord Chancellor with access to all records.

As a result, it seems that Sir James Tyrell has been cemented in the collective conscience as the undoubted murderer of the ‘Princes in the Tower’ because of two dramatic narratives; More’s and Shakespeare’s. With More’s History published in the middle of the sixteenth century, it went on to become the key source for Shakespeare’s Richard III in 1593.

Until further evidence is forthcoming, or new materials uncovered, we must conclude that there are no grounds to support the validity (or veracity) of Sir James Tyrell’s alleged confession to the murder of King Edward IV’s sons.

However, what we can perhaps conclude from this analysis is that some connection was made between Tyrell and the sons of Edward IV at, or before, the time of Tyrell’s death. Could this connection be explained by the two pardons granted to Tyrell by King Henry in the summer of 1486, which in turn added an indirect degree of credence to what the king later ‘gave out’ in respect of Tyrell’s guilt? This supposition will be explored in a forthcoming Bulletin when The Missing Princes Project will announce its initial results, and two remarkable new discoveries.

1. For Tyrell’s commissions for Edward IV, see CPR 1467-1477 (1900), pp 492, 606.

2. Caroline Halsted, Richard III (1844), first published 1977 (reprint 1980), Vol 2, p.187, fn.3. My thanks to Marie Barnfield for alerting me to this quote that may have first appeared in Halsted. From: P. Vergilii, Anglicæ Historiæ libri XXVI (1534), p.569.

3. Denys Hay, The Anglica Historia of Polydore Vergil 1485-1537 (1950), p.13, from Latin fn.3, lines 3-9, ‘aliquo terrarium secreto’. My thanks to project member, Christopher Tinmouth, for his transcription of Hay and for undertaking the search for the original quote in Vergil’s first edition of 1534. Please note that for whatever reason Hay does not translate this key line into his English account for Vergil. Ann Wroe, Perkin: A Story of Deception (2004), p.73, also renders this as ‘some secret land’.

4. James Gairdner, Letters and Papers Illustrative of the Reigns of Richard III and Henry VII (1863), Vol II, pp 335-6, ‘XVII - Fines Levied on Warbeck’s Adherents’.

5. W.E. Hampton, ‘Sir James Tyrell: with some notes on the Austin Friars London and those buried there’, Richard III: Crown and People (1985), pp 204-5, Ricardian, (December 1978), Vol.IV, No.63, p.12. My thanks to John Dike of The Missing Princes Project’s Coldridge Research Group for alerting me to this and for a copy of Speke’s will. See also: p.214, (Ricardian, p.19), for James Haute’s support of Richard III. Haute was a former Esquire of the Body to Edward IV and a close relation to the Woodville family and a number of the rebels in the October 1483 rebellion, which spread the rumour of the boys’ deaths.

6. Ann Wroe, Perkin: A Story of Deception (2004), p.177.

7. Sir Frederick Madden, Documents Relating to Perkin Warbeck, with Remarks on his History (1837), p.25. Also see: Archaeologia, Vol 27, (1838), p.178. From a long and very detailed written report to Henry VII from Bernard de Vignolles, a Frenchman, dated at Rouen, 14 March 1495 (modern calendar 1496). Vignolles records: ‘the said Prior of St. John, has been two or three times, once a twelve-month, to the house of Sir Thomas Tirel, to inquire after news, and discussed various matters between them, and among other things the Prior began to speak how King Edward had formerly been in the said house, to which the said Sir Thomas replied, that it was true, and that the King had formerly made good cheer there, and that he hoped, by God’s will, that the son of the said Edward should make the like cheer there, and that the said house had been built with the money of France … and during the above discourse the said Bernard and Sir John Thonge [Thweng?] were present.’

8. Horrox, ONDB, Tyrell family.

9. Wroe, Perkin, pp 177-178,185, 228.

10. Horrox, ONDB, Tyrell family.

11. Audrey Williamson, The Mystery of the Princes (1978), p.91. The tradition records: ‘that the princes and their mother Elizabeth Woodville lived in the hall by permission of the uncle’ and goes back ‘well before the eighteenth century and was handed down from generation to generation.’ In 1973 it had been revealed to Williamson during her researches by a relative of the Tyrell family, Kathleen Margaret Drewe.

12. Annette Carson, Richard III: The Maligned King (2008), p.183.

13. Rev W.H. Sewell, ‘Memoires of Sir James Tyrell’ (1878), The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, Vol. 5, Part Two, pp 125-180 (p.179).

14. For Tyrell’s children, see main article fn.11.

15. C.S.L. Davies, ‘Information, Disinformation and Political Knowledge under Henry VII and Early Henry VIII’, Historical Research 85 (2012), p.242. Matthew Lewis, The Survival of the Princes in the Tower (2017), pp 29-31. For a transcript of John Rastell’s Pastime, pp 29-30. A full extract is also available below.

16. Sewell, p.152. Dibdin, Pastime, pp, 293-294, 297. Rastell states: ‘Immediately after his coronation, the grudge, as well of the lords as of the commons, greatly increased against him [King Richard], because the common fame went that he had secretly murdered the two sons of his brother, King Edward IV in the Tower of London.’ Sir James Tyrell is not mentioned in Rastell’s account for any of the reigns including Richard III’s (pp 297-299), although a ‘Sir Thomas Tyrell’ is recorded as being beheaded after the (second) battle of St Albans (1461), p.274. This is a mistake for Sir Thomas Kyriell of Kent (1396–1461).

Possible likeness of Sir James Tyrell from walls of St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk. Image: Philip J. Turner, 1933

Signature of Sir James Tyrell, Redgrave Hall, Suffolk muniments, 8 January 1501, from Rev. W.H. Sewell, Memoirs of Sir James Tyrell (1878), p.167

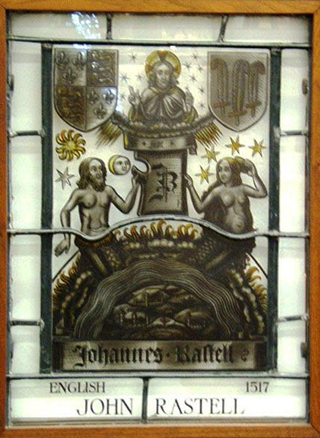

Tyrell Family Coat of Arms from window, St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk. Boar’s Head with Peacock Tail. Image: courtesy of St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk

Yorkist Sunnes in Splendour with White Roses from window. Image courtesy of St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk

Yorkist White Roses, and Martlet Bird, from window. Image: courtesy of St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk

Arms of Sir James Tyrell with Martlet Bird. A martlet denoted Tyrell’s position as a younger son of Sir William Tyrell. A martlet in English heraldry is a mythical bird without feet which never roosts and is continuously on the wing. It therefore represents an allegory for continuous effort. Image: Philippa Langley.

Large white Yorkist rose in window. Image courtesy of St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk

The Tyrell Knot Badge on walls of chapel. Image courtesy of St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk

St. Nicholas’ Chapel, Gipping, Suffolk. Image courtesy of Kerry Baker

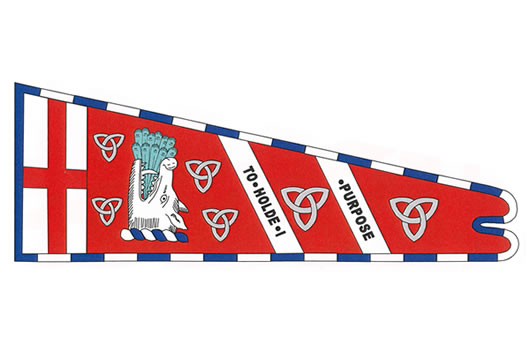

The Pastime of People by John Rastell (1529) – brother-in-law of Sir Thomas More

In terms of its importance to the traditional story of Sir James Tyrell’s confession to the murder of the ‘Princes in the Tower’ (as above), an extract of this significant work by John Rastell is now published here in order to make it more widely available.

John Rastell (c.1475–1536) was an author, printer, publisher and patron of the theatre. He printed plays, music, jokes, legal and religious tracts, as well as a history of England. His printing shop was located on the south side of (old medieval) St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Rastell married Sir Thomas More’s sister, Elizabeth.

Image: stained glass panel, former Kent Library building.

Our very grateful thanks to Alec Marsh, editor of the Ricardian Bulletin magazine, for his kind permission to publish Tyrell’s Confession here for you.